This post might be created with help from AI tools and carefully reviewed by a human (Anthor Kumar Das). For more on how we use AI on this site, check out our Editorial Policy.

Do Bees Hibernate or Migrate? How They Survive Every Season

Every winter, many new beekeepers ask the same question: “Do bees hibernate or migrate?”. I had the same confusion when I first started beekeeping. Watching my bees vanish from sight as the temperature dropped made me wonder if they flew somewhere warmer or simply went to sleep inside the hive.

After spending a few seasons observing my beehives, I discovered the truth. Honey Bees neither migrate like birds nor truly hibernate like bears. Instead, they have their own smart way of surviving cold and harsh weather. It’s one of nature’s most fascinating teamwork stories.

That’s what I am going to explain to you in this blog post. This blog post will cover the following major topics:

- Do Bees Hibernate?

- Do Bees Migrate?

- How do Bees Survive in Different Seasons?

- About Hibernation or Migration of Different Bee Species

- How to Help Bees Survive the Winter

So, by the end of this article, you will have the knowledge of everything you need to know about hibernation and the migration of bees.

Do Bees Hibernate?

Bees do not hibernate in the same way as many animals. When winter comes, they do not fall into a deep sleep or move away from their home. Instead, bees slow down their activity and stay inside the hive to survive the cold months together.

Honey bees use a method called clustering. When the outside temperature drops, thousands of worker bees form a tight ball around the queen. Their goal is to keep her warm and safe.

The bees on the outer edge of the cluster act as insulation, while the bees in the center vibrate their bodies to generate heat. As the outer bees get cold, they slowly rotate toward the middle, and the warmer ones move out. This constant movement keeps the whole cluster alive through freezing weather.

Inside the hive, the temperature in the center of the cluster stays around 30°c to 35°c, even when it is freezing outside. The bees feed on stored honey for energy, which helps them produce warmth. They do not leave the hive during this time except on rare warmer days when they make short cleansing flights.

From my own experience, when I checked my hives on a mild winter day, I could hear a gentle humming sound inside. It was the sound of the cluster working together. They were not asleep but carefully saving energy and protecting the queen until spring returned. This is how bees make it through the cold season without true hibernation.

Then, Where Do Carpenter Bees and Bumble Bee Go in The Winter?

Like me, most of you might also have seen that when winter arrives, carpenter bees suddenly disappear. However, they actually do not completely disappear. Either they emerge in a new location or die.

In most cases, they emerge in a new location that is comparatively warmer. As they don’t produce honey, they don’t have a reserve of food.

As a result, when winter arrives, carpenter bees have to emerge to a new location. If you consider this phenomenon as carpenter bee hibernation, you might not be wrong in a sense.

In the case of bumble bees, the newly born queen builds a pollen-filled and fat reserves cell and goes inside it. She relies on the reserved pollen and nectar and is unlikely to come out during the winter.

Most other members of the old colony will fail to survive the winter and die.

Do Bees Migrate?

Unlike birds or butterflies, most bees do not migrate. They stay close to their nesting area all year and rely on stored food to survive seasonal changes. Migration means moving long distances to find better weather or food sources, but bees are built to adapt locally rather than travel far.

Honey bees, for example, never leave their hive during cold months. Their home is permanent, and it holds everything they need. They survive winter by eating stored honey and keeping their hive warm as a group. Moving long distances would risk losing their food and queen, so migration is not part of their nature.

However, a few wild or tropical bee species may show short-distance movement when their environment changes. Some stingless bees and Africanized honey bees shift their nests to nearby locations if their food supply becomes low or the nest site gets damaged. This is not true migration but more like relocation within the same region.

Note: Some ground bees, like bumble bees, sweat bees, and carpenter bees, can move to a comparatively warmer location before winter. But they do not migrate over very long distances. However, as they move to a new location, you can call this behaviour as migration as well.

In simple terms, honey bees prefer to stay and survive where they are rather than migrate. Their strength lies in teamwork and adaptability. While other creatures travel across continents, honey bees focus on protecting their hive, managing food, and waiting patiently for better conditions to return.

However, Carpenter bees, bumble bees, and some other ground bees can migrate to a subcontinent for winter preparation.

How Bees Survive Winter

Winter is the hardest season for bees, especially in colder regions. When flowers disappear and the temperature drops, bees cannot collect nectar or pollen. Instead of leaving the hive, they depend on teamwork and stored food to survive until spring.

Understanding how bees handle winter helps new beekeepers take better care of their colonies.

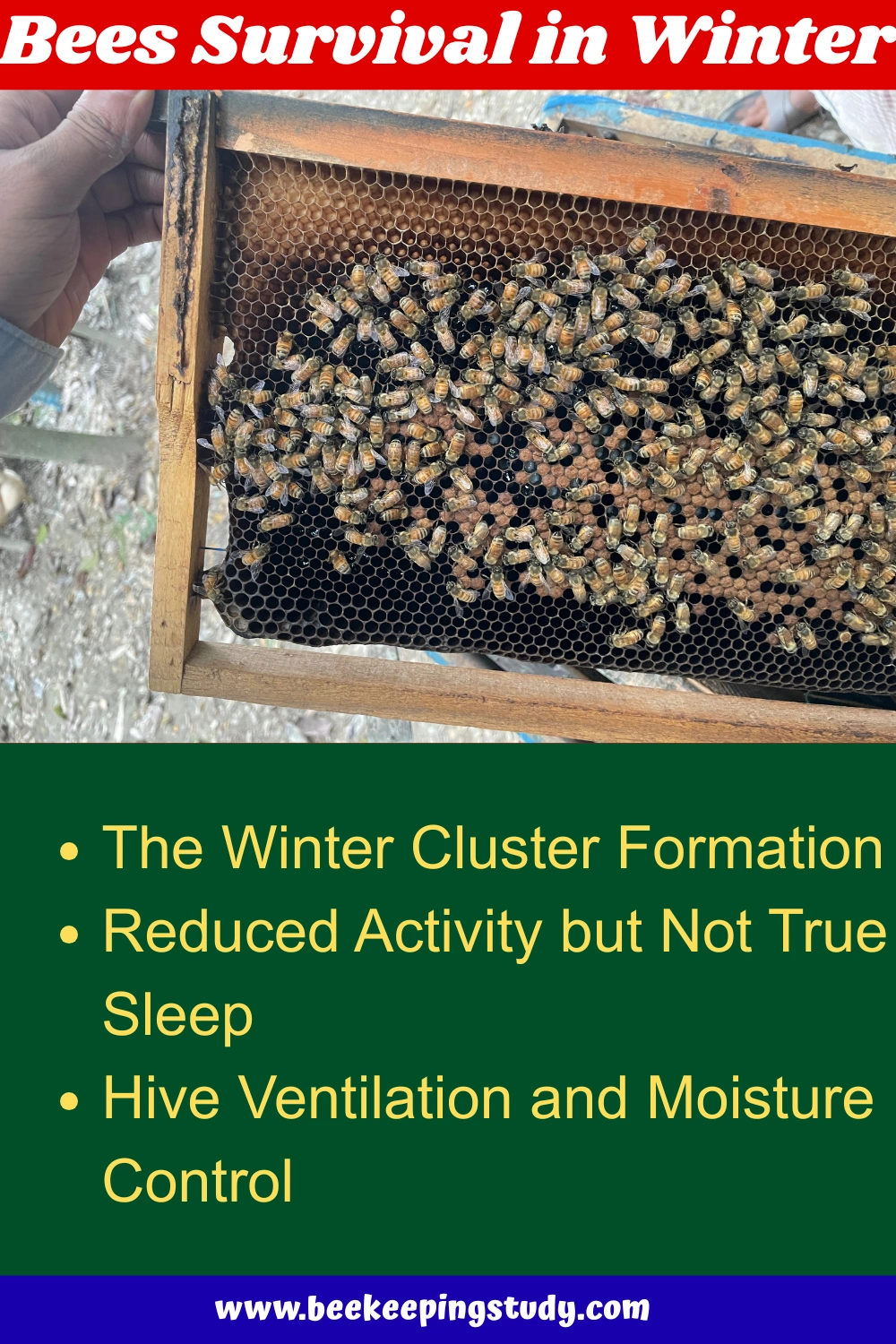

The Winter Cluster Formation

As soon as the temperature starts to fall below 30°c, bees gather close together around the queen to form what is called a winter cluster. It looks like a living ball of bees packed tightly together inside the hive. The worker bees on the outside form a shield, while those in the middle vibrate their flight muscles to generate heat.

This constant motion keeps the inner temperature of the cluster around 30 to 35 degrees Celsius, even when the air outside is freezing.

They have to do this in order to protect the queen by any means. Because a honey bee colony can’t survive the winter without the queen.

The bees take turns moving in and out of the cluster so that none of them get too cold. They feed on stored honey to fuel this heat production. Without enough honey reserves, the colony can starve even if they manage to stay warm. This is why beekeepers always make sure their hives have enough food before winter starts.

I also noticed that when the temperature drops below 15°c there is zero traffic around the beehives. Means all the bees are inside the hive and trying their level best to survive the winter.

The bees in the cluster tries to be as tight and close as possible when the temperature falls below 10°c. As a result, bees have to work very hard in such situations. Proper Beehive winterization is really crucial for a region where temeperature can fall below this temperature.

So, responsible beekeepers always take necessary steps to winterize a beehive properly. This is to help the bees work comparatively less and survive the winter easily.

Reduced Activity but Not True Sleep

Bees do not sleep during winter. They remain semi-active inside the hive. Their activity level drops, but they are still alert and working together to keep the cluster warm.

Worker bees take turns generating heat and resting. The queen stays in the center, protected and surrounded by warm workers.

If you place your ear near the hive on a mild day, you may hear a soft humming sound. That quiet hum means the colony is alive and healthy. It is the sound of bees vibrating their wings in rhythm to keep everyone safe until the first warm days of spring.

Hive Ventilation and Moisture Control

Good ventilation is one of the most important parts of winter hive care. Without airflow, moisture builds up inside the hive from the bees’ breathing and the warmth of the cluster. This moisture can drip down and chill the bees, leading to disease or death. I learned that more colonies die from moisture than cold.

To help your bees, keep the hive dry but not drafty. Use a small upper entrance or moisture board to let damp air escape while trapping enough heat inside. Also, slightly tilt the hive forward so condensation can drain away instead of freezing on the frames. These small steps can make a huge difference in keeping your bees safe and comfortable through winter.

What Happens to Bees in Other Seasons

Bees do not just work hard in summer and rest in winter. Their behavior changes through every season. Understanding what happens in spring, summer, and fall helps you predict what your bees need and when they need it. Each part of the year has its own rhythm inside the hive.

Spring – Growth and New Life

Spring is the season of renewal for bees. As the weather warms up, bees leave the hive to collect pollen and nectar from early flowers. The queen starts laying eggs again, and the brood nest expands quickly. The colony population grows fast during this time.

Beekeepers should inspect their hives more often in spring. Make sure the queen is healthy and that there is enough space for new brood and honey storage.

This is also the season when bees prepare to swarm. Swarming is natural but can reduce honey production, so it is important to manage hive space and monitor swarm cells carefully.

If you see any overpopulated colony, make sure to split that beehive into 2 new beehives to prevent swarming away.

This is the time when carpenter bees come out from winter hibernation and become visible in most areas. Bumble bees also start building nests and laying eggs to start a new colony. This is why you might see a heavy traffic of bumble bees, carpenter bees, sweat bees, and other ground bees in this season.

Summer – Peak Activity

Summer is the busiest time for bees. The colony reaches its largest size, and worker bees spend long hours gathering nectar and pollen. This is when honey production is at its highest. Foragers fly in and out of the hive from sunrise to sunset, bringing back food to feed the brood and fill the honeycomb.

During this time, bees build up reserves for the next winter. They store extra honey, maintain the hive, and care for the growing brood. Beekeepers often harvest honey during late summer, but should always leave enough for the bees to survive the colder months.

Carpenter bees started moving to a new location at the end of summer. But Bumble bees keep expanding their colony by raising broods.

Fall – Preparing for Cold

When the days grow shorter and flowers begin to fade, bees know it is time to prepare for winter. The queen slows down egg laying, and brood production decreases. Worker bees start focusing on protecting food stores and sealing cracks in the hive with propolis to keep out drafts.

I have discovered that honey bees become very aggressive in the fall. They don’t like much interaction in this season.

Beekeepers should reduce hive inspections in the fall and avoid disturbing the cluster. It is also a good time to check food levels and treat for pests like mites before winter arrives. Bees enter the cold months smaller in number but stronger as a group, ready to survive together until spring returns.

Hibernation vs. Migration in Different Bee Species

Not all bees behave the same way when seasons change. Some hibernate to survive the cold, while others stay active or even move short distances when their environment changes.

Understanding how different bee species adapt helps you appreciate how nature designed each of them to fit its surroundings.

| Bee Type | Behavior in Winter | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Honey Bees | Stay in the hive and form a warm cluster around the queen. | Do not migrate. Survive on stored honey and teamwork to maintain warmth. |

| Bumble Bees | Only the queens hibernate in the soil until spring. | The rest of the colony dies before winter. Queens start new colonies in spring. |

| Solitary Bees | Larvae stay sealed inside their nests through winter. | Adults emerge in spring when flowers bloom. |

| Carpenter Bees | Hide in wooden tunnels or old nests during cold weather. | Hibernate alone until temperatures rise again. |

| Africanized and Tropical Bees | May move short distances when food sources dry up. | Show limited migration but stay within the same region; remain active in warm climates. |

Thus, while some bee species truly hibernate, others stay semi-active or adapt differently depending on their climate. Honey bees are the best example of teamwork-based hibernation, while wild or tropical bees rely more on environmental movement to survive changing seasons.

How Climate Affects Honey Bee Survival

Bees adapt their survival habits based on the climate where they live. Temperature, rainfall, and flower availability all influence how bees behave during different seasons.

A hive in a snowy region acts very differently from one in a sunny tropical area. Understanding these patterns helps beekeepers make better choices for hive care in any location.

In cold climates, bees rely on cluster hibernation to stay alive. When temperatures drop close to freezing, honey bees form a tight cluster around their queen and generate heat by vibrating their wings.

They stay inside the hive for months, feeding on stored honey to keep the colony warm. Without this teamwork, they would not survive the winter.

In warm climates, bees do not experience true hibernation. Instead, they remain active but slow down slightly during cooler or rainy periods.

Since flowers are available for most of the year, bees in tropical countries can collect nectar and pollen almost continuously. Beekeepers in these areas may notice that their colonies grow faster and produce honey nearly all year long.

For example, bees in tropical countries like Bangladesh, India, Brazil, and Thailand are active through most months. They may only rest briefly during heavy rain or during the peak winter season. They do not cluster much for heat the way bees in cold regions do. Their survival depends on constant foraging rather than stored food.

I have noticed bee cluster inside my beehives when the temperature in my region falls below 15°c.

However, climate change is starting to affect these natural patterns. Unpredictable weather and sudden temperature shifts can confuse bees, disrupting their seasonal rhythm.

Early blooming or delayed winters make it harder for bees to find food at the right time. Some wild bee species have already shown changes in flight patterns and short-distance migration due to these changes in the environment.

Beekeepers can help by keeping hives insulated in colder regions and providing water or shade during extreme heat. Paying attention to weather trends and adjusting hive management by season will make a big difference in how well your bees survive and thrive each year.

How Beekeepers Help Bees During Winter

Bees need help from beekeepers before winter. Winter care is about warmth, food, and moisture control. I keep things simple and focus on what protects the cluster without disturbing it.

- Feed when food is low: If the hive feels light, give sugar syrup during warm spells or switch to fondant or dry sugar when it is cold. Place feed above the cluster so bees can reach it without breaking their group.

- Reduce the entrance: A smaller entrance helps keep heat in and keeps mice, wasps, and cold drafts out. Add a mouse guard where needed. Make sure to keep a perfect dimension for the beehive entrance reducer.

- Check weight instead of opening: Heft the hive from the back to judge food stores. If it feels too light, add feed. Avoid full inspections in cold weather.

- Add insulation in cold regions: Use insulation boards or simple wraps to slow heat loss. Keep ventilation in mind so moisture can escape. You can use a beehive Quilt Box as well in this case.

- Control moisture: Use an upper entrance or a moisture board. Slightly tilt the hive forward so condensation drains away.

- Inspect Less: Choosing the ideal timing for beehive inspection is crucial for every season. Especially in winter, you must try to inspect less. Only inspect and provide sugar syrup when it is a comparatively less cold day.

Personal tip: I prefer using a simple insulation wrap and an upper vent. It keeps my hives dry and warm all winter. However, you must decide whether a moisture board or a quilt box is ideal for your beehive winterization based on your environmental conditions.

Bottom Line: Do Bees Hibernate or Migrate?

So, what have you learn so far about Do bees hibernate or migrate? In short, though honey bees do not hibernate or migrate, they do not come out from the hive during colder months.

On the other hand, carpenter bees, bumble bees, and some other solitary bees might hibernate or migrate in a sense. Not similar to other animals like birds, bears, and so on.

If you are a beekeeper, you must be aware of what you have to do to help your bees survive every season. Always give higher priority to food reservation and hive moisture control for the winter survival of honey bees.